Would “Big Daddy” Gardiner (Expressway) Buy the Banks Today?

Last month, at a Rotary Club meeting, I found myself sitting next to someone I hadn’t met before. After asking about my profession, he leaned in a few minutes later and said, “Is it true that to get rich, you should only buy Canadian banks?”

Well, I know of at least one person who rode that tip to many, many millions of dollars.

For most Toronto drivers, “the Gardiner” conjures up images of traffic and gridlock. Yet, unlike Yonge or Dundas Streets, if you lived in the city before his death in 1983, it wouldn’t have been all that hard to meet the person it’s named after face-to-face.

Fred Gardiner — or “Big Daddy”, as the press liked to call him — was a lawyer, politician, and relentless stock buyer. He was so bullish on Canadian stocks that he sometimes accepted share certificates as payment from his legal clientele. During the Great Depression, he used all his savings to buy the Bank of Toronto. When it merged with Dominion Bank in 1955, it became the Toronto-Dominion Bank as we know it today.

By then, Gardiner’s portfolio had grown to the equivalent of $3 million in today’s dollars — his biggest holding being the Toronto-Dominion Bank. Those shares alone would now be worth about $250 million, plus another $90 million in dividends received along the way. (Disclosure: while certain clients are shareholders of TD, neither Jeff Pollock nor Sunni Schneider directly or indirectly hold a financial interest in TD as shareholders.)

Investors can’t expect that kind of growth again. Banking today looks very different now than a hundred years ago. Howard Green wrote in his book Banking on America that the Canadian banks in the 1950s were “sleepy, stuffy and small-minded.”

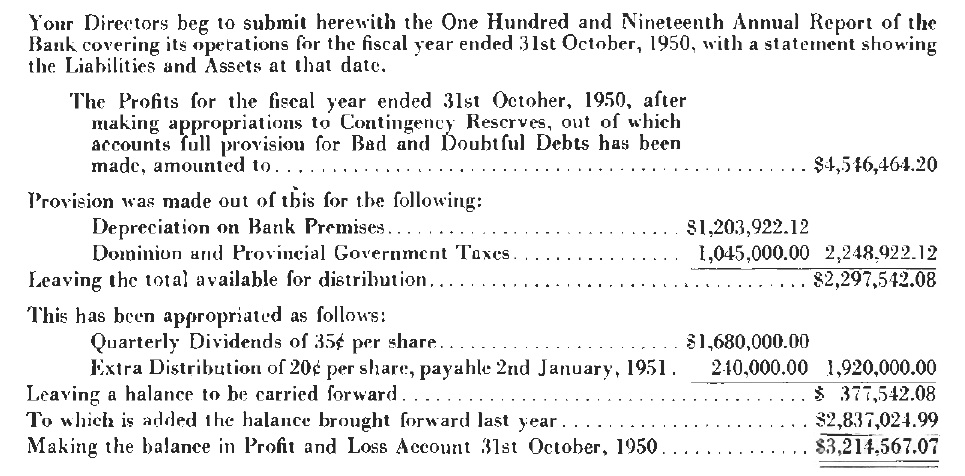

We dug up a copy of Scotiabank’s annual report from 1950 to see just how much things have changed. (Disclosure: Jeff Pollock and Sunni Schneider directly and indirectly hold a financial interest in BNS as shareholders.) That year, it celebrated the opening of 18 new branches, bringing its total to 367, and reported assets of $818 million — a tiny fraction of the $1.4 trillion it manages today. Back then, banks pretty much only took deposits and made loans. Today, between mutual fund fees, investment banking revenue, credit card interest, and auto loans, banks have exploded in size and receive a much broader source of revenue.

Still, some things haven’t changed. Banks here remain conservative, albeit because the regulators make sure it stays that way. And, banks continue to pay reliable, steadily rising dividends. In 1950, Scotiabank yielded 4.3%. Now, it’s a 5.1% yield.

Our favourite bank was the Canadian Western Bank because of its growth prospects. Because it was acquired by National Bank earlier this year, however, we sold it for about 160% (including dividends) above our purchase price. Today, our preferred bank to own is Scotiabank. It trades at about 12x earnings — over 12% cheaper than the median Canadian bank, not to mention it’s the least expensive of its peers — and its dividend yield is roughly one-third higher than the other banks. Scotiabank is deliberately reshaping its international footprint, concentrating resources on Canada, the U.S., and Mexico while scaling back from lower-return foreign markets. Last quarter, wealth management grew at double digits, global banking earnings are improving, and credit trends remain stable across retail and commercial portfolios.

So, would “Big Daddy” buy the banks today?

Probably yes — but not to chase outsized growth. He’d be collecting dividends but watching the share prices grow at a slower rate than in his day.

-written by Jeff Pollock

DISCLAIMER: Unless otherwise noted, all publications have been written by a registered Advising Representative and reviewed and approved by a person different than its preparer. The opinions expressed in this publication are for general informational purposes only and are not intended to represent specific advice. Any securities discussed are presumed to be owned by clients of Schneider & Pollock Management Inc. and directly by its management. The views reflected in this publication are subject to change at any time without notice. Every effort has been made to ensure that the material in this publication is accurate at the time of its posting. However, Schneider & Pollock Wealth Management Inc. will not be held liable under any circumstances to you or any other person for loss or damages caused by reliance of information contained in this publication. You should not use this publication to make any financial decisions and should seek professional advice from someone who is legally authorized to provide investment advice after making an informed suitability assessment.