Why Aren’t Bond Prices Yielding to Higher Geopolitical Risk?

With so much geopolitical unrest abroad, you would expect a rush to safety. Normally, that means long-term bond prices catch a bid (causing their respective yields to fall). However, that’s not the case this time.

Over the last month, the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield rose from 4.5% to 5.0% earlier this week. Today, it’s hovering around 4.8%. Remember that bond prices and yields move in opposite directions – when yields rise, that’s because prices are declining.

Why exactly are long-term bond yields rising as geopolitical risk escalates?

U.S. Fed Chair Jay Powell opined last week on the subject, saying:

[The recent jump in long-term bond yields are not] about expectations of higher inflation. It’s also not mainly about shorter term policy moves. You can look at the 2-year [Treasury yield], for example. The 2-year has moved up a little bit since September but really the move is in longer-run bonds. So, it’s really happening in term premiums, which is the compensation for holding longer run securities, and not principally a function of the market looking at near term fund rates.

He went on to add his two cents on why rates are increasing.

Markets and analysts are seeing the resilience of the economy to high interest rates. They’re revising their view of the overall strength of the economy. … There may be a heightened focus on fiscal deficits. … [Quantitative tightening] could be part of it. Another one you hear very often is the changing correlation between bonds and equities. If we’re going forward into a world of more supply shocks rather than demand shocks, that could make bonds a less attractive hedge to equities.

Most of the run-up in longer-term yields took place in September amid strong economic data. This was before the U.S. Congress showed their speaker to the door and the Israeli-Humas conflict began. We don’t think the market is concerned about government deficits, though it probably should be.

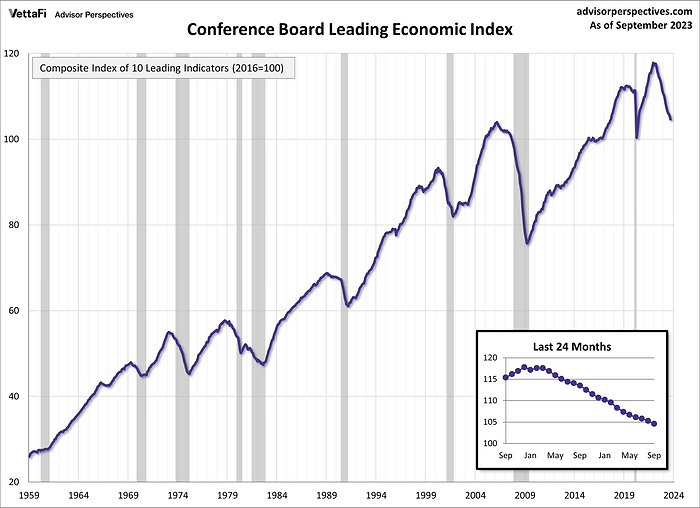

Instead, we think long-term yields have surged on the belief that a resilient economy will require higher rates for a long future. However, the market has mispriced future growth and a mild recession will take place in 2024. In September, 9 of the 10 leading economic indicators were flat or declined, suggesting that a recession is forthcoming. The recent surge in long-term rates will weaken growth further.

Have a look at this chart below. The grey bars indicate a recession. Each recession since 1959 was accurately predicted by the Conference Board’s Leading Economic Index and this time is no different.

A weaker economy will require the central banks to cut rates. This bodes well for stock prices, particularly in 2024. We continue to favour the contrarian dividend-paying securities that will catch a stronger bid as rates fall.

-written by Jeff Pollock

DISCLAIMER: Unless otherwise noted, all publications have been written by a registered Advising Representative and reviewed and approved by a person different than its preparer. The opinions expressed in this publication are for general informational purposes only and are not intended to represent specific advice. Any securities discussed are presumed to be owned by clients of Schneider & Pollock Management Inc. and directly by its management. The views reflected in this publication are subject to change at any time without notice. Every effort has been made to ensure that the material in this publication is accurate at the time of its posting. However, Schneider & Pollock Wealth Management Inc. will not be held liable under any circumstances to you or any other person for loss or damages caused by reliance of information contained in this publication. You should not use this publication to make any financial decisions and should seek professional advice from someone who is legally authorized to provide investment advice after making an informed suitability assessment.