With Inflation at 8.6%, What Happens Next?

For anyone under the age of 60, this inflationary environment is probably something you’ve read about but never actually experienced.

Friday’s U.S. inflation report showed that during May, prices grew +8.6% compared to one year before. This was the highest inflation rate since 1981. April’s print was +8.3%, down from March’s +8.5% rate. The hope was that inflation was sequentially decreasing, or at least not accelerating. Analysts had estimated May’s rate would be a more modest +8.3%, unchanged from April.

Price increases were broad-based across the board, ranging from food (+10.1% year-over-year) to energy (+34.6%) to new and used vehicles (+12.6% and +16.1%, respectively) to services (+5.2%).

Economists like to look at “core inflation”, which excludes food and energy. That figure was +6.0% compared to May 2021. Granted, food and energy are volatile commodities, but for those of us living in the real world, they’re rather important.

The U.S. Federal Reserve meets this week and is widely expected to hike their benchmark rate by 50 basis points (one basis point equal 0.01%). After yesterday’s report, a handful of strategists suggested 75 basis points might be on the table. The market will be most attentive to Fed Chair Jay Powell’s guidance for future policy action in September.

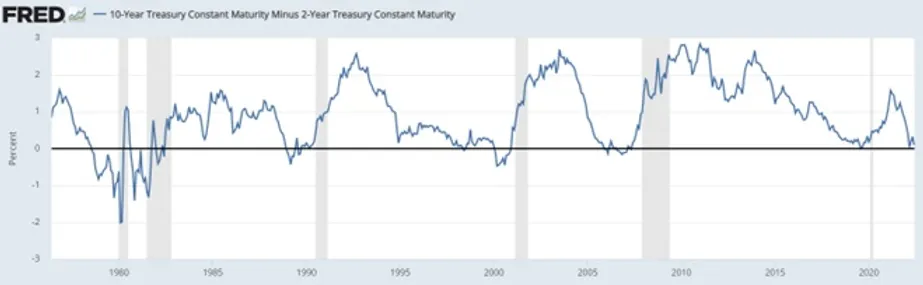

Meanwhile, the bond market is suggesting a recession may be on the horizon.

We’ve spoken on our podcasts before about “the yield curve”, which is simply the difference between the longer-term 10-year and the shorter-term 2-year Treasury bond rates. Any time the short term-rate exceeds the long-term rate, a recession historically follows. It doesn’t happen right away – usually there’s a lag of several quarters, but as you can see below, we’re getting awfully close to an inverted curve. The shaded areas represent recessions since 1976. Right now, the 10-year yield exceeds the 2-year only slightly (9 basis points to be exact, or 0.09%).

While consumer confidence is still reasonably high, it’s beginning to fade. It hasn’t dropped this quickly since the pandemic began in 2020. Before that, you must go back to 2011 when we were all shaking our heads at Greece during the European debt crisis.

Our view is that these higher food and gas prices are going to deter the consumer from spending, which will contract the economy and alleviate the need for central banks to be as aggressive in their quest to raise rates as the market presently fears.

-written by Jeff Pollock

DISCLAIMER: Unless otherwise noted, all publications have been written by a registered Advising Representative and reviewed and approved by a person different than its preparer. The opinions expressed in this publication are for general informational purposes only and are not intended to represent specific advice. Any securities discussed are presumed to be owned by clients of Schneider & Pollock Management Inc. and directly by its management. The views reflected in this publication are subject to change at any time without notice. Every effort has been made to ensure that the material in this publication is accurate at the time of its posting. However, Schneider & Pollock Wealth Management Inc. will not be held liable under any circumstances to you or any other person for loss or damages caused by reliance of information contained in this publication. You should not use this publication to make any financial decisions and should seek professional advice from someone who is legally authorized to provide investment advice after making an informed suitability assessment.