Could the AI Stocks Follow Cisco’s Fortune?

Most investors underestimate their appetite for risk. Before we open a new account, we send out a brief survey with several questions. The answers give us a better idea about our soon-to-be client’s comfort with volatility and experience with the market. One of our questions asks which of the scenarios below is most preferred:

- A portfolio that grows 5% per year in a good market but falls 5% in a bad market;

- A portfolio that grows 10% per year in a good market but falls 10% in a bad market;

- A portfolio that grows 20% per year in a good market but falls 20% in a bad market; or

- A portfolio that grows 30% per year in a good market but falls 30% in a bad market.

Everyone would surely like to see their assets grow 30% in a single year. However, we’ve never had someone tell us they’re comfortable taking the risk of losing 30% in a bad market. In other words, we’ve yet to have a client select option #4.

This blog is not about any one particular stock. Rather, there is a crowded trade right now with many of the gains coming from high growth technology companies. It seems like many are chasing the first half of option #4 from our questionnaire.

But could the second half of option #4 ever come true?

On May 15, 2000, Fortune magazine ran a feature article gushing about Cisco Systems. Gracing its CEO on the magazine’s cover, the publisher asked, “Is John Chambers the Best CEO on Earth?” The article went on to describe Chambers as “brilliant” and suggested the stock was a must-own, even writing in the opening paragraph that “No matter how you cut it, you’ve got to own Cisco.”

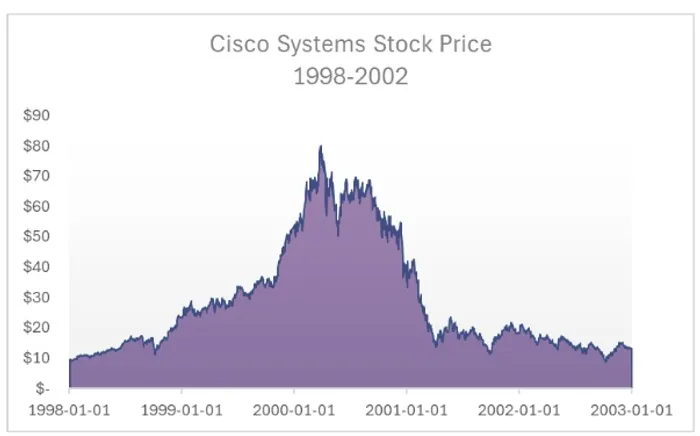

At the time, shareholders involved with Cisco had taken quite the ride. Those that bought the stock a year earlier had doubled their money; people who invested two years prior had now quadrupled their investment.

Shortly before the Fortune article was published, Cisco became the world’s most valuable company, boasting a $550 billion market capitalization as its stock price hit $80/share.

In 2000, the analysts all had similarly bullish expectations for the upcoming year. After all, the Internet was booming and Cisco provided the routers and networking infrastructure that made it all possible. Earnings forecasts for 2001 ranged from 71 to 81 cents per share, up from the 53 cents earned the year before. As late as November 2000, even Cisco’s Chief Financial Officer said publicly that the company expected their actual earnings to be 2 to 5 cents higher than the analysts’ estimates.

If Cisco were to deliver in 2001 – let’s call it 86 cents in earnings per share for the year – that pegs its earnings valuation at about 1.1x its growth rate (finance nerds call this a “PEG ratio”, which takes the price-to-earnings ratio [70x in this case] and divides it by the earnings growth rate [+62% here]). In case you’re wondering, Apple and Microsoft both trade today at 2.7x next year’s growth rate.

While Cisco’s market capitalization hit $550 billion in 2000 (or $1 trillion today after adjusting for inflation), Apple and Microsoft are both worth over $3.2 trillion today.

Then it all hit the fan.

Demand for Cisco’s routers and networking equipment began to experience a sharp slowdown as the “dot com” bubble burst.

Cisco never did deliver on those rosy 2001 forecasts made by analysts a year earlier.

Instead, for the first time in years, Cisco disappointed the street’s expectations. While the company posted 18% revenue growth in 2001 – a figure most companies would envy – it wasn’t the 55% growth like they achieved in 2000. Nor was it the 50% that analysts originally expected at the beginning of the year. Cisco earned 41 cents per share for the entire year, far less than the 71 to 81 cents per share originally expected back in 2000.

Consequently, the stock tanked. By 2002, the stock price had plummeted by 86% from the day the Fortune magazine cover story called the stock a must-own. Investors had completed a full circle between 1998 and 2002.

Investing in companies with very optimistic future growth rates accompanies high risk and high reward. Sure, everyone wants growth. But are you willing to live with the downside if something unexpected goes wrong?

Before concentrating your portfolio in stocks that require significant future growth to justify today’s valuation, be sure to weigh both the upside as well as the downside.

-written by Jeff Pollock

DISCLAIMER: Unless otherwise noted, all publications have been written by a registered Advising Representative and reviewed and approved by a person different than its preparer. The opinions expressed in this publication are for general informational purposes only and are not intended to represent specific advice. Any securities discussed are presumed to be owned by clients of Schneider & Pollock Management Inc. and directly by its management. The views reflected in this publication are subject to change at any time without notice. Every effort has been made to ensure that the material in this publication is accurate at the time of its posting. However, Schneider & Pollock Wealth Management Inc. will not be held liable under any circumstances to you or any other person for loss or damages caused by reliance of information contained in this publication. You should not use this publication to make any financial decisions and should seek professional advice from someone who is legally authorized to provide investment advice after making an informed suitability assessment.